Getting close to nature through architecture comes in many forms. Some homes take to glass facades , dissolving the barrier between the outdoors and inside, then some homes feature blueprints that wrap around trees, incorporating their canopies and trunks into the lay of the house. Omri Cohen, a student designer at Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, has a different idea. Cohen developed the Living Shell, an architectural shell built by growing jute, felt, and wheatgrass into a form of a textile that’s laid over a bamboo frame.

Turning to textile technology, Living Shell was born from Cohen’s quest to evolve layers of wheatgrass root systems into elastic, textile materials. Settling on the shell’s curvilinear structural shape, the wheatgrass textile wraps over its bamboo frame, forming layers of insulation and shade while it continues to grow. Cohen found durability in the inexpensive building material he developed from jute, felt, and wheatgrass. Layering the different roots together in a pattern that allows room for sustained growth periods, the textile’s thickness and durability increase over time as the roots continue to interlace and grow. While he has yet to build a life-size Living Shell, Cohen crafted 1:10 models to demonstrate the feasibility of introducing the Living Shell into rural and urban environments alike. Connecting the structure to an irrigation system, the textile overwrap would most likely receive nourishment from a programmed watering method.

While Living Shell functions like a house, it would more likely offer natural refuge hubs for small animals to gather nesting materials from and inhabit. Additionally, Cohen developed Living Shell so that urban dwellers and rural farmers have the opportunity to watch nature in action, for all of its natural growth, regenerative, and decay processes.

Designer: Omri Cohen

Layered around a bamboo frame, Cohen’s Living Shell is made from a textile developed from jute, felt, and wheatgrass.

Before building its life-size debut, Cohen created tiny 1:10 models of Living Shell.

Following tests to show how wheatgrass root systems grew through textile sheets, Cohen settled on some that could be woven together into a single textile sheet.

Cohen found a textile sheet that he could sew together and integrate the seeds of jute, felt, and wheatgrass.

Wheatgrass growing through the textile sheets.

The growth process of wheatgrass shows that the textile’s thickness would increase with continued irrigation.

Making Something Out of Nothing

In our cult of the new and the shiny, it’s sometimes refreshing to remember that it’s possible to make new things out of old things that look old. No, seriously, it’s possible. And Jan Korbes Garbage Architecture has many projects to prove it. Coming from the Gordon Matta-Clark school of architecture, Jan Korbes follows a lot of threads at once. There are a lot of small furniture pieces involving scrap wood and recycled car tires. Some are interesting, some you’ve seen before, but in every instance he doesn’t stop experimenting.

Where it starts to get really interesting is when the objects start to become architecture, or pieces of architecture. The Zee Stair is a great example: an old harbor pole is sawn again to become a beautiful, unexpected stair. Sinus Stairs II takes this a step farther by recycling old doors to create a screen-like staircase, one that begins to take on the mass and shape of a building. Optrek Tranvaal takes recovered doors from other projects and recycles them into a skylight/balcony cut not unlike some of Matta-Clark’s late proposals, where the envelope of the building is cut to create something entirely new. This is someone we’re going to be checking in on from time to time. We can’t wait for the truly big projects to begin.

Designer: Jan Korbes Garbage

This air sealed work pod was designed to let employees return to office post quarantine

We all have a new work-from-home routine that everyone has had to adapt to overnight. Now some companies can afford to let employees continue working from home till a vaccine is made but there are many others who are open and functioning with bare minimum staff because their work is not digital. Just like working from home brought to light issues we didn’t have, working in the office during or after pandemic will have its own set of new issues and that is what designers are aiming to solve with concepts with Qworkntine.

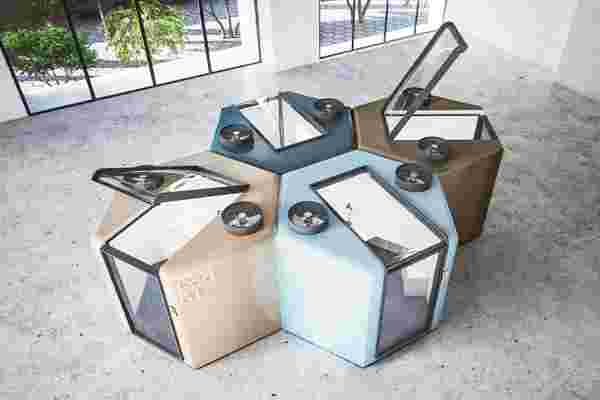

The non-essential companies have to open up at some point to keep the economy (and our income) running. Qworkntine is an air-tight pod system that wants to make working in offices safe while we figure out long-term solutions. It protects the employees and can make it easy to monitor how many employees are in per square meter of the space – it also makes contact tracing convenient in larger offices. Its hexagonal shape lets companies arrange it in any format to suit their physical office – it is like assembling a beehive to keep all the bees healthy and happy! It can be customized to fit right-angled corners and can be elongated as per the needs.

This conceptual work pod features an automatic handle-free acrylic door that is controlled by facial recognition. It also includes ventilation fans and air purifiers to keep a continuous flow of air that is safe to breathe. The designer envisions the Qworkntine pod to be made from hygienic, non-porous materials that will be easy to clean and disinfect. The skylight makes it better for those who may not enjoy tight spaces. Winner of the DNA Paris Design Awards in the Responsible Design category, this design highlights that for the sake of our health (and wealth), we may have to adapt to new work environments. Instead of cubicles, we might have pods and that is basically the same size as having an apartment in Manhattan – say hi to the new home of ‘work-from-home’!

Designer: Moahmed Radwan

This article was sent to us using the ‘ Submit A Design ’ feature.

We encourage designers/students/studios to send in their projects to be featured on Yanko Design!